The Yellow fever virus

The yellow fever virus is found in tropical and subtropical areas of Africa and South America. The virus is spread to people by the bite of an infected mosquito. Yellow fever is a very rare cause of illness in U.S. travelers. Illness ranges from a fever with aches and pains to severe liver disease with bleeding and yellowing skin (jaundice). Yellow fever infection is diagnosed based on laboratory testing, a person’s symptoms, and travel history. There is no medicine to treat or cure infection. To prevent getting sick from yellow fever, use insect repellent, wear long-sleeved shirts and long pants, and get vaccinated.

Causes

Yellow fever is caused by a virus that is spread by the Aedes aegypti mosquito. These mosquitoes thrive in and near human habitations where they breed in even the cleanest water. Most cases of yellow fever occur in sub-Saharan Africa and tropical South America.

Humans and monkeys are most commonly infected with the yellow fever virus. Mosquitoes transmit the virus back and forth between monkeys, humans or both.

When a mosquito bites a human or a monkey infected with yellow fever, the virus enters the mosquito’s bloodstream and circulates before settling in the salivary glands. When the infected mosquito bites another monkey or human, the virus then enters the host’s bloodstream, where it may cause illness.

Signs and symptoms

Once contracted, the yellow fever virus incubates in the body for 3 to 6 days. Many people do not experience symptoms, but when these do occur, the most common are fever, muscle pain with prominent backache, headache, loss of appetite, and nausea or vomiting. In most cases, symptoms disappear after 3 to 4 days.

A small percentage of patients, however, enter a second, more toxic phase within 24 hours of recovering from initial symptoms. High fever returns and several body systems are affected, usually the liver and the kidneys. In this phase people are likely to develop jaundice (yellowing of the skin and eyes, hence the name ‘yellow fever’), dark urine and abdominal pain with vomiting. Bleeding can occur from the mouth, nose, eyes or stomach. Half of the patients who enter the toxic phase die within 7 – 10 days.

Symptoms

During the first three to six days after you’ve developed yellow fever — the incubation period — you won’t experience any signs or symptoms. After this, the infection enters an acute phase and then, in some cases, a toxic phase that can be life-threatening.

Acute phase

Once the infection enters the acute phase, you may experience signs and symptoms including:

- Fever

- Headache

- Muscle aches, particularly in your back and knees

- Sensitivity to light

- Nausea, vomiting or both

- Loss of appetite

- Dizziness

- Red eyes, face or tongue

These signs and symptoms usually improve and are gone within several days.

Toxic phase

Although signs and symptoms may disappear for a day or two following the acute phase, some people with acute yellow fever then enter a toxic phase. During the toxic phase, acute signs and symptoms return and more-severe and life-threatening ones also appear. These can include:

- Yellowing of your skin and the whites of your eyes (jaundice)

- Abdominal pain and vomiting, sometimes of blood

- Decreased urination

- Bleeding from your nose, mouth and eyes

- Slow heart rate

- Liver and kidney failure

- Brain dysfunction, including delirium, seizures and coma

The toxic phase of yellow fever can be fatal.

Diagnosis

Yellow fever is difficult to diagnose, especially during the early stages. A more severe case can be confused with severe malaria, leptospirosis, viral hepatitis (especially fulminant forms), other haemorrhagic fevers, infection with other flaviviruses (such as dengue haemorrhagic fever), and poisoning.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing in blood and urine can sometimes detect the virus in early stages of the disease. In later stages, testing to identify antibodies is needed (ELISA and PRNT).

Populations at risk

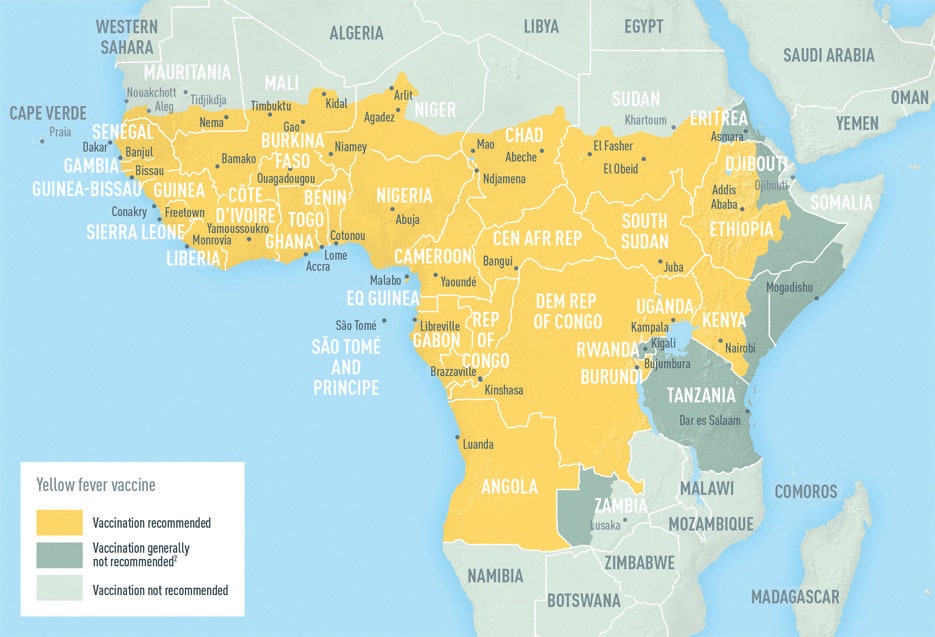

Forty-seven countries in Africa (34) and Central and South America (13) are either endemic for, or have regions that are endemic for, yellow fever. A modelling study based on African data sources estimated the burden of yellow fever during 2013 was 84 000–170 000 severe cases and 29 000–60 000 deaths.

Occasionally travellers who visit yellow fever endemic countries may bring the disease to countries free from yellow fever. In order to prevent such importation of the disease, many countries require proof of vaccination against yellow fever before they will issue a visa, particularly if travellers come from, or have visited yellow fever endemic areas.

In past centuries (17th to 19th), yellow fever was transported to North America and Europe, causing large outbreaks that disrupted economies, development and in some cases decimated populations.

Areas/Regions mostly at risk

Transmission

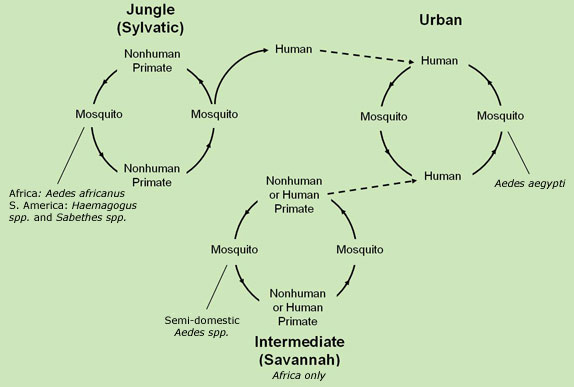

The yellow fever virus is an arbovirus of the flavivirus genus and is transmitted by mosquitoes, belonging to the Aedes and Haemogogus species. The different mosquito species live in different habitats – some breed around houses (domestic), others in the jungle (wild), and some in both habitats (semi-domestic).

Yellow fever virus is an RNA virus that belongs to the genus Flavivirus. It is related to West Nile, St. Louis encephalitis, and Japanese encephalitis viruses. Yellow fever virus is transmitted to people primarily through the bite of infected Aedes or Haemagogus species mosquitoes. Mosquitoes acquire the virus by feeding on infected primates (human or non-human) and then can transmit the virus to other primates (human or non-human). People infected with yellow fever virus are infectious to mosquitoes (referred to as being “viremic”) shortly before the onset of fever and up to 5 days after onset.

There are 3 types of transmission cycles:

- Sylvatic (or jungle) yellow fever: In tropical rainforests, monkeys, which are the primary reservoir of yellow fever, are bitten by wild mosquitoes of the Aedes and Haemogogus species, which pass the virus on to other monkeys. Occasionally humans working or travelling in the forest are bitten by infected mosquitoes and develop yellow fever. The jungle (sylvatic) cycle involves transmission of the virus between non-human primates (e.g., monkeys) and mosquito species found in the forest canopy. The virus is transmitted by mosquitoes from monkeys to humans when humans are visiting or working in the jungle.

- Intermediate yellow fever: In this type of transmission, semi-domestic mosquitoes (those that breed both in the wild and around households) infect both monkeys and people. Increased contact between people and infected mosquitoes leads to increased transmission and many separate villages in an area can develop outbreaks at the same time. This is the most common type of outbreak in Africa. In Africa, an intermediate (savannah) cycle exists that involves transmission of virus from mosquitoes to humans living or working in jungle border areas. In this cycle, the virus can be transmitted from monkey to human or from human to human via mosquitoes.

- Urban yellow fever: Large epidemics occur when infected people introduce the virus into heavily populated areas with high density of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes and where most people have little or no immunity, due to lack of vaccination or prior exposure to yellow fever. In these conditions, infected mosquitoes transmit the virus from person to person. The urban cycle involves transmission of the virus between humans and urban mosquitoes, primarily Aedes aegypti. The virus is usually brought to the urban setting by a viremic human who was infected in the jungle or savannah.

Treatment

Good and early supportive treatment in hospitals improves survival rates. There is currently no specific anti-viral drug for yellow fever but specific care to treat dehydration, liver and kidney failure, and fever improves outcomes. Associated bacterial infections can be treated with antibiotics.

Prevention

1. Vaccination

Vaccination is the most important means of preventing yellow fever.

The yellow fever vaccine is safe, affordable and a single dose provides life-long protection against yellow fever disease. A booster dose of yellow fever vaccine is not needed.

Several vaccination strategies are used to prevent yellow fever disease and transmission: routine infant immunization; mass vaccination campaigns designed to increase coverage in countries at risk; and vaccination of travellers going to yellow fever endemic areas.

In high-risk areas where vaccination coverage is low, prompt recognition and control of outbreaks using mass immunization is critical. It is important to vaccinate most (80% or more) of the population at risk to prevent transmission in a region with a yellow fever outbreak.

There have been rare reports of serious side-effects from the yellow fever vaccine. The rates for these severe ‘adverse events following immunization’ (AEFI), when the vaccine provokes an attack on the liver, the kidneys or on the nervous system are between 0 and 0.21 cases per 10 000 doses in regions where yellow fever is endemic, and from 0.09 to 0.4 cases per 10 000 doses in populations not exposed to the virus (1).

The risk of AEFI is higher for people over 60 years of age and anyone with severe immunodeficiency due to symptomatic HIV/AIDS or other causes, or who have a thymus disorder. People over 60 years of age should be given the vaccine after a careful risk-benefit assessment.

People who are usually excluded from vaccination include:

- infants aged less than 9 months;

- pregnant women – except during a yellow fever outbreak when the risk of infection is high;

- people with severe allergies to egg protein; and

- people with severe immunodeficiency due to symptomatic HIV/AIDS or other causes, or who have a thymus disorder.

In accordance with the International Health Regulations (IHR), countries have the right to require travellers to provide a certificate of yellow fever vaccination. If there are medical grounds for not getting vaccinated, this must be certified by the appropriate authorities. The IHR are a legally binding framework to stop the spread of infectious diseases and other health threats. Requiring the certificate of vaccination from travellers is at the discretion of each State Party, and it is not currently required by all countries.

2. Vector control

The risk of yellow fever transmission in urban areas can be reduced by eliminating potential mosquito breeding sites, including by applying larvicides to water storage containers and other places where standing water collects.

Both vector surveillance and control are components of the prevention and control of vector-borne diseases, especially for transmission control in epidemic situations. For yellow fever, vector surveillance targeting Aedes aegypti and other Aedes species will help inform where there is a risk of an urban outbreak.

Understanding the distribution of these mosquitoes within a country can allow a country to prioritize areas to strengthen their human disease surveillance and testing, and to consider vector control activities. There is currently a limited public health arsenal of safe, efficient and cost-effective insecticides that can be used against adult vectors. This is mainly due to the resistance of major vectors to common insecticides and the withdrawal or abandonment of certain pesticides for reasons of safety or the high cost of re-registration.

Historically, mosquito control campaigns successfully eliminated Aedes aegypti, the urban yellow fever vector, from most of Central and South America. However, Aedes aegypti has re-colonized urban areas in the region, raising a renewed risk of urban yellow fever. Mosquito control programmes targeting wild mosquitoes in forested areas are not practical for preventing jungle (or sylvatic) yellow fever transmission.

Personal preventive measures such as clothing minimizing skin exposure and repellents are recommended to avoid mosquito bites. The use of insecticide-treated bed nets is limited by the fact that Aedes mosquitos bite during the daytime.

3. Epidemic preparedness and response

Prompt detection of yellow fever and rapid response through emergency vaccination campaigns are essential for controlling outbreaks. However, underreporting is a concern – the true number of cases is estimated to be 10 to 250 times what is now being reported.

WHO recommends that every at-risk country have at least one national laboratory where basic yellow fever blood tests can be performed. A confirmed case of yellow fever in an unvaccinated population is considered an outbreak. A confirmed case in any context must be fully investigated. Investigation teams must assess and respond to the outbreak with both emergency measures and longer-term immunization plans.

More tips on prevention of Yellow Fever

The most effective way to prevent infection from Yellow Fever virus is to prevent mosquito bites. Mosquitoes bite during the day and night. Use insect repellent, wear long-sleeved shirts and pants, treat clothing and gear, and get vaccinated before traveling, if vaccination is recommended for you.

Prevent Mosquito Bites

Use Insect Repellent

Use Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)-registered insect repellentsexternal icon with one of the active ingredients below. When used as directed, EPA-registered insect repellents are proven safe and effective, even for pregnant and breastfeeding women.

- DEET

- Picaridin (known as KBR 3023 and icaridin outside the US)

- IR3535

- Oil of lemon eucalyptus (OLE)

- Para-menthane-diol (PMD)

- 2-undecanone

Find the right insect repellent for you by using EPA’s search toolexternal icon.

Tips for babies and children

- Dress your child in clothing that covers arms and legs.

- Cover strollers and baby carriers with mosquito netting.

- When using insect repellent on your child:

- Always follow label instructions.

- Do not use products containing oil of lemon eucalyptus (OLE) or para-menthane-diol (PMD) on children under 3 years old.

- Do not apply insect repellent to a child’s hands, eyes, mouth, cuts, or irritated skin.

- Adults: Spray insect repellent onto your hands and then apply to a child’s face.

Tips for Everyone

- Always follow the product label instructions.

- Reapply insect repellent as directed.

- Do not spray repellent on the skin under clothing.

- If you are also using sunscreen, apply sunscreen first and insect repellent second.

Natural insect repellents (repellents not registered with EPA)

- We do not know the effectiveness of non-EPA registered insect repellents, including some natural repellents.

- To protect yourself against diseases spread by mosquitoes, CDC and EPA recommend using an EPA-registered insect repellent.

- Choosing an EPA-registered repellent ensures the EPA has evaluated the product for effectiveness.

- Visit the EPA website to learn more.external icon

Wear long-sleeved shirts and long pants

Treat clothing and gear

- Use permethrin to treat clothing and gear (such as boots, pants, socks, and tents) or buy permethrin-treated clothing and gear.

- Permethrin is an insecticide that kills or repels mosquitoes.

- Permethrin-treated clothing provides protection after multiple washings.

- Read product information to find out how long the protection will last.

- Do not use permethrin products directly on skin.

Take steps to control mosquitoes indoors and outdoors

- Use screens on windows and doors. Repair holes in screens to keep mosquitoes outdoors.

- Use air conditioning, if available.

- Stop mosquitoes from laying eggs in or near water.

- Once a week, empty and scrub, turn over, cover, or throw out items that hold water, such as tires, buckets, planters, toys, pools, birdbaths, flowerpots, or trash containers.

- Check indoors and outdoors.

Prevent mosquito bites when traveling overseas

- Choose a hotel or lodging with air conditioning or screens on windows and doors.

- Sleep under a mosquito bed net if you are outside or in a room that does not have screens.

- Buy a bed net at your local outdoor store or online before traveling overseas.

- Choose a WHOPES-approved bed net: compact, white, rectangular, with 156 holes per square inch, and long enough to tuck under the mattress.

- Permethrin-treated bed nets provide more protection than untreated nets.

- Do not wash bed nets or expose them to sunlight. This will break down the insecticide more quickly.

Yellow Fever Vaccine

A safe and effective yellow fever vaccine has been available for more than 80 years.

- A single dose provides lifelong protection for most people.

- The vaccine is a live, weakened form of the virus given as a single shot.

- Vaccine is recommended for people aged 9 months or older and who are traveling to or living in areas at risk for yellow fever virus in Africa and South America.

- Yellow fever vaccine may be required for entry into certain countries.

- Vaccination requirements and recommendations for specific countries are available on the CDC Travelers’ Health page.

Should I take the Vaccine or NOT?

Yellow fever vaccine is recommended for people who are 9 months old or older and who are traveling to or living in areas at risk for yellow fever virus in Africa and South America.

For most people, a single dose of yellow fever vaccine provides long-lasting protection and a booster dose of the vaccine is not needed. However, travelers going to areas with ongoing outbreaks may consider getting a booster dose of yellow fever vaccine if it has been 10 years or more since they were last vaccinated. Certain countries might also require a booster dose of the vaccine; visit Travelers’ Health for information on specific country requirements.

Talk to your healthcare provider to determine if you need a yellow fever vaccination or a booster shot before your trip to an area at risk for yellow fever.

Some people may have an increased risk of developing a reaction to the vaccine, but may still benefit from being vaccinated. These people, or their guardians, should talk to a healthcare provider about getting vaccinated:

- Between 6 and 8 months old

- Over 60 years old

- Pregnant

- Breastfeeding

A few people should not get the vaccine. Vaccine is not recommended for people who are:

- Allergic to a vaccine or something in the vaccine (like eggs)

- Aged 6 months or younger

- Organ transplant recipients

- Diagnosed with a malignant tumor

- Diagnosed with thymus disorder associated with abnormal immune function

- Diagnosed with a primary immunodeficiency

- Using immunosuppressive and immunomodulatory therapies

- Showing symptoms of HIV infection or CD4+ T-lymphocytes less than 200/mm3 (less than 15% of total lymphocytes in children aged 6 years or younger)

Reactions to Yellow Fever Vaccine

Reactions to yellow fever vaccine are generally mild and include headaches, muscle aches, and low-grade fevers. Rarely, people develop severe, sometimes life-threatening reactions to the yellow fever vaccine, including:

- Allergic reaction, including difficulty breathing or swallowing (anaphylaxis)

- Swelling of the brain, spinal cord, or the surrounding tissues (encephalitis or meningitis)

- Guillain-Barré syndrome, an uncommon sickness of the nervous system in which a person’s own immune system damages the nerve cells, causing muscle weakness, and sometimes, paralysis.

- Internal organ dysfunction or failure

If you recently received the yellow fever vaccination and develop fever, headache, tiredness, body aches, vomiting, or diarrhea, see your healthcare provider.

Some people may have an increased risk of developing a reaction to the vaccine, but may still benefit from being vaccinated. These people, or their guardians, should talk to a healthcare provider about getting vaccinated:

- Between 6 and 8 months old

- Over 60 years old

- Pregnant

- Breastfeeding

Yellow Fever Vaccine, Pregnancy, & Conception

Yellow fever vaccine has been given to many pregnant women without any apparent adverse effects on the fetus. However, since yellow fever vaccine is a live virus vaccine, it poses a theoretical risk.

Pregnant women should avoid or postpone travel to an area where there is risk of yellow fever. If travel cannot be avoided, discuss vaccination with your doctor.

While a two week delay between yellow fever vaccination and conception is probably adequate, a one month delay has been advocated as a more conservative approach.

If, for some reason, a woman is vaccinated during pregnancy, she is unlikely to have any problems from the vaccine and her baby is very likely to be born healthy.

Complications

Yellow fever results in death for 20% to 50% of those who develop severe disease. Complications during the toxic phase of a yellow fever infection include kidney and liver failure, jaundice, delirium, and coma.

People who survive the infection recover gradually over a period of several weeks to months, usually without significant organ damage. During this time a person may experience fatigue and jaundice. Other complications include secondary bacterial infections, such as pneumonia or blood infections.

WHO response

In 2016, two linked urban yellow fever outbreaks – in Luanda (Angola) and Kinshasa (Democratic Republic of the Congo), with wider international exportation from Angola to other countries, including China – have shown that yellow fever poses a serious global threat requiring new strategic thinking. The Eliminate Yellow Fever Epidemics (EYE) Strategy was developed to respond to the increased threat of yellow fever urban outbreaks with international spread. Steered by WHO, UNICEF, and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, EYE supports 40 countries and involves more than 50 partners.

The global EYE Strategy is guided by three strategic objectives:

- protect at-risk populations.

- prevent international spread of yellow fever.

- contain outbreaks rapidly.

These objectives are underpinned by five competencies of success:

- affordable vaccines and sustained vaccine market;

- strong political commitment at global, regional and country levels;

- high-level governance with long-term partnerships;

- synergies with other health programmes and sectors; and

- research and development for better tools and practices.

The EYE strategy is comprehensive, multi-component and multi-partner. In addition to recommending vaccination activities, it calls for building resilient urban centres, planning for urban readiness, and strengthening the application of the International Health Regulations (2005).

The EYE partnership supports yellow fever high and moderate risk countries in Africa and the Americas by strengthening their surveillance and laboratory capacity to respond to yellow fever cases and outbreaks. EYE partners also support the implementation and sustainability of routine immunization programmes and vaccination campaigns (preventive, pre-emptive, reactive) whenever and wherever needed.

To guarantee a rapid and effective response to outbreaks, an emergency stockpile of 6 million doses of yellow fever vaccine, funded by Gavi, is continually replenished. This emergency stockpile is managed by the International Coordinating Group for Vaccine Provision, for which WHO serves as secretariat.

It is expected that by the end of 2026, more than 1 billion people will be protected against yellow fever through vaccination.

Key facts

- Yellow fever is an acute viral haemorrhagic disease transmitted by infected mosquitoes. The “yellow” in the name refers to the jaundice that affects some patients.

- Symptoms of yellow fever include fever, headache, jaundice, muscle pain, nausea, vomiting and fatigue.

- A small proportion of patients who contract the virus develop severe symptoms and approximately half of those die within 7 to 10 days.

- The virus is endemic in tropical areas of Africa and Central and South America.

- Large epidemics of yellow fever occur when infected people introduce the virus into heavily populated areas with high mosquito density and where most people have little or no immunity, due to lack of vaccination. In these conditions, infected mosquitoes of the Aedes aegypti species transmit the virus from person to person.

- Yellow fever is prevented by an extremely effective vaccine, which is safe and affordable. A single dose of yellow fever vaccine is sufficient to grant sustained immunity and life-long protection against yellow fever disease. A booster dose of the vaccine is not needed. The vaccine provides effective immunity within 10 days for 80-100% of people vaccinated, and within 30 days for more than 99% of people vaccinated.

- Good supportive treatment in hospitals improves survival rates. There is currently no specific anti-viral drug for yellow fever.

- The Eliminate Yellow fever Epidemics (EYE) Strategy launched in 2017 is an unprecedented initiative. With more than 50 partners involved, the EYE partnership supports 40 at-risk countries in Africa and the Americas to prevent, detect, and respond to yellow fever suspected cases and outbreaks. The partnership aims at protecting at-risk populations, preventing international spread, and containing outbreaks rapidly. By 2026, it is expected that more than 1 billion people will be protected against the disease.